LARPing Leonard Cohen

"Oh yes, of course I knew Leonard. Very nice man. Very quiet."

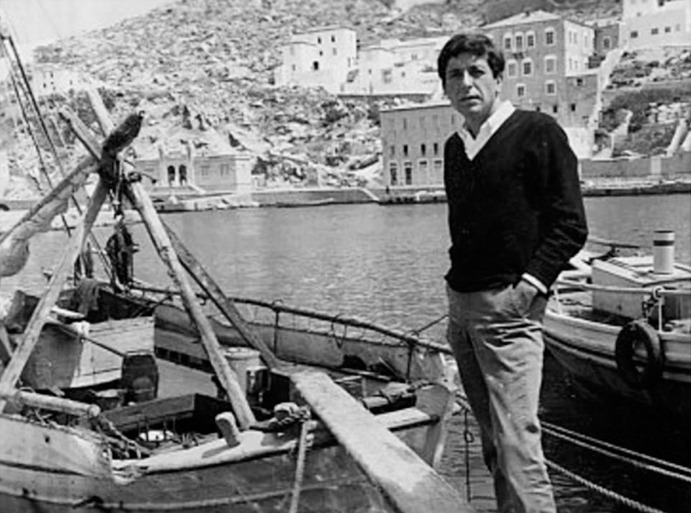

TheVine is sitting in the Ostria Taverna, a pleasant little restaurant on the Greek island of Hydra. Hydra, as any self-respecting Leonard Cohen obsessive knows, is the island where Cohen bought a house during the 1960s to serve as his private writing retreat, far from the temptations of New York City or the distractions of his native Montreal. It's also an easy hour-long ride on the hyrdofoil from Athens, making it a pretty attractive destination for even a brief detour from the mainland.

I'm here for a month, though — my plan is to hole up and work on a novel. Even before Cohen made Hydra something of a destination for writers and bohemians during the 1960s and 1970s, the island had a literary history disproportionate to its size and general notability — Henry Miller's The Colossus of Maroussi was set here, and the island's long been home to a wealth of artistically-inclined types, both Hellenic and from overseas.

So decamping to Hydra to write for a month seems like a gloriously, dizzily romantic thing to do. Because I'm doing this in the middle of winter (January 2012, to be precise), it's also surprisingly affordable — I score a room for €20 a night, which doesn't include breakfast but does include getting my washing done by the proprietor's mother if I ask politely enough. The room's Spartan but pleasant, and comes with a kitchen and a little electric stove that covers the preparing basic necessities of life (ie. tea, coffee and basic dinners.) It also comes with a beautiful view of the bare mountainside that dominates most of Hydra's surface area.

There's something quite evocative about being in a place that's essentially a holiday destination during offseason. Most of the restaurants and bars are closed for the winter, and the only people around are locals and the island's dwindling supply of long-term expats. The latter are a fascinating bunch — in the course of a month, I meet a guy who used to play in John Squire's post-Stone Roses project The Seahorses, several painters, a fellow literary Cohenphile and a fascinating old chap who used to produce for the BBC and may or may not also have been a spy. Most of them are old — the only people buying here these days, apparently, are cashed-up US east coast types looking for holiday houses. But still, for now, at least, the vestiges of the island's bohemian past can be found if you know where to look.

The community centres around the aforementioned Ostria Taverna, run by the redoubtable Stathis, who is as quick with a political opinion as he is with a serve of delicious local calamari or a barbecued pork chop. Greece is changing, he tells me over coffee one morning, but Hydra is doing its best not to, because being unchanged is what keeps it alive. And certainly to outward appearances, the island looks just as it might have done in 1960, when Cohen spent the princely sum of $1500 on his house, or in the 19th century, or whenever. The buildings are all wrought out of stone that's quarried straight from the island itself. There are no cars — you walk everywhere, and if you need to transport something you can't carry, you do so by requisitioning the services of one of the swarthy types with donkeys who gather at the port every morning, waiting for supplies to come from the mainland.

Apart from donkeys and starstruck creative types, the island's single largest demographic group is cats. They're everywhere — the majority hang out down at the port, waiting for the fishing boats to come in, but pretty much anywhere you walk on Hydra, you're going to be accompanied by a bevy of feline companions. I befriend one particular creature, who makes it his business to join me on my regular morning walks. There's plenty to explore on the island, but I usually end up wandering through Kamini, Hydra's "other" village, which a 15-minute walk from the harbour and almost entirely deserted. The deeper you wend your way into the landscape, the more you discover — on one of my walks, I come across what appears to be some sort of ruined villa, an entire building sinking back into the hillside. Its only inhabitant these days appears to be a stern-faced and rather regal donkey.

It was to Kamini, apparently, that Leonard used to retreat during the summers when the crowds in town started to recognize him and pester him for photos and autographs. Most of the island's long-time residents remember him and speak warmly of him, but it turns I'm at least a decade too late to stand any chance of meeting the man himself — "He stopped coming in 1997," one of the locals tells me over dinner one night. "People started to bother him too much." It's probably just as well — after all, what would you say to Leonard Cohen? I'd probably just stand and gape.

So I don't get to talk to Leonard Cohen. In fact, I basically don't talk to anyone — I speak very little Greek, so my only interactions are with the crew at the taverna, which I visit two or three times a week, and a whispered "efharisto" to the lady from whom I buy my groceries. The solitude is curiously liberating. The days stretch and blur together. One day it snows, which is virtually unheard of at sea level. A week later a storm comes in that's sufficiently powerful to knock out all the power on the island for most of the day. I sit and write until my laptop battery dies, and then I sit by candlelight and listen to the wind and watch the lightning fork over the bay.

When the rain finally stops I head to the taverna, which has its own generator, and make good on my promise to Stathis to sing a couple of songs for him and his patrons. In keeping with the theme of the island, I try for "Famous Blue Raincoat" — inevitably, though, I forget the chords, and eventually settle for a couple of renditions of Jens Lekman songs, which go down well with the locals. I drink too much red wine and wake up with my one and only Hydran hangover.

On my last morning, I walk all the way up to the Monastery of Prophet Elias, a 90-minute hike uphill along a path that's a testament to the Orthodox Church's fondness for building its retreats in the remotest locations possible. The last 500 metres or so is a straight climb up an old marble staircase that looks like it's ascending straight to heaven, and the view back down across the water is astoundingly beautiful, vivid colours against a sunbleached landscape, the water of the Saronic gulf the same deep blue as the stripes on the Greek flag.

It starts to rain as a I wend my way back down to the harbour, and the smell of fresh rain on pine needles and cypress trees is indescribably evocative. I feel close to the past, somehow, like this place has some connection with a lineage of culture and history. A sacred place, of sorts.

Or perhaps that's overly starry-eyed nonsense, and this place is like any other — what you make it. Either way, I leave with 80,000 words — a pretty solid month's work, I guess, although I have very little frame of reference as to how prolific real novelists are. I bid my goodbyes to the Ostria crew and (making a brief detour via Athens, just in time to get caught up in a riot), and then head back to reality. Now, a couple of months later, the whole thing seems like some impossibly romantic dream. But then, as Cohen himself wrote about Hydra, "The years are flying past and we all waste so much time wondering if we dare to do this or that. The thing is to leap, to try, to take a chance."

Post a comment